The Paradox of Buridan's Ass

Published:

Betwixt the rock and the hard place

In my post where I gave the world (you’re welcome!) the word animalisine, I referred to the French philosopher Jean Buridan, as does Sheldon in this clip from the always entertaining Big Bang Theory:

Where to start? Contrary to what Julie Andrews’ Maria in the Sound of Music suggests, let’s start at the end:

“Should two courses be judged equal, then the will cannot break the deadlock, all it can do is to suspend judgement until the circumstances change, and the right course of action is clear. — Jean Buridan, c. 1340”

Well that was, as Maria did say, a very good place to start. During my knowledge quest into Buridan’s Ass, I was frequently informed of it being a philosophical paradox. OK, not unlike an ass, I’ll bite. A philosophical paradox you say. I think I understand what philosophy1 is, but what is this paradox you speak of? Maria, you were right. Let’s start at the very beginning.

Paradox:

- a seemingly absurd or self-contradictory statement that is or may be true

- a self-contradictory proposition, such as: ‘I always tell lies’

- a person or thing exhibiting apparently contradictory characteristics

- an opinion that conflicts with common belief

- I’d also like to add that Paradox was the first database software I used back in the DOS days. I notice it is still going strong as part of Corel’s WordPerfect Office package, an alternative to Microsoft Office.

During my early secondary school education, I spent a couple of English lessons learning figures of speech. I understood that a paradox was similar to an oxymoron (which we can have fun with in a later post) but had more words to it. Accordingly, they can be convoluted and hard to understand. An oxymoron can be contained within two words: clearly confusing right?

After nailing paradox as a figure of speech, a history lesson during that same schooling period had me stumbling over this essay question:

‘The Agrarian Revolution of the 1830s was a socio-economic paradox. Explain.’

…and explain I did. Alas no records of that essay remain. I believe the gist of my explanation was that the revolution should have lead to better wealth distribution amongst the population thus leaving fewer people in poverty. It did not and there’s the paradox. Happy to be corrected and/or educated on this by my loyal readership.

Armed with those recollections, I still struggled to understand the paradox element of Buridan’s Ass.

Some simple paradox examples to ease the brain into the right mindset:

- I must be cruel to be kind. (From William Shakespeare’s Hamlet)

- Please ignore the notice.

- I can resist anything except temptation. (From Oscar Wilde’s Lady Windemere’s Fan)

- They must go to war to make peace.

- Deep down he’s really shallow.

- This is the beginning of the end. (Oddly, Shakespeare uses this in his Midsummer Night’s Dream but for a different meaning.)

With your brain in gear, time for some chewy philosophical paradoxes. The gentleman who ‘invented’ the paradox, Eubulides of Miletus, managed to give us seven initial examples, grouped by four themes, straight off the bat. His most famous being The Liar paradox - along the lines of “what I am saying now is a lie”. A variation of this paradox was used in the 1986 fantasy movie Labyrinth. Sarah (played by Jennifer Connelly) is confronted by two guarded doors - one of which leads to safety. The guard of one door always lies. The guard of the other door always tells the truth. With time ticking Sarah needs to work out which door will lead her onwards by asking a question which will provide the answer she needs (i.e. which door is the right door to open). She manages to work out what to ask…can you?2

Eubulides’ sôritês paradox (The Heap) concerns the measures around language and vagueness: so what’s not to like about that? This paradox considers a heap of sand from which you remove grains of sand. If your heap starts with 10,000 grains of sand and you keep on removing one grain down to a single remaining grain of sand is that single grain of sand still a heap? If not, at which point did the heap cease to be? Now that’s a paradox I not only can get my teeth into but also understand. So perhaps it may help with Buridan and his Ass?

Next up, a testudine paradox from a different Greek philosopher (who paradoxically lived around 100 years before the ‘inventor’ of the paradox Eubulides): Zeno’s Achilles and the tortoise:

In this paradox, Achilles races a tortoise. Achilles gives the tortoise a 100 meter head start because Achilles is a cocky fast runner. In the time it takes Achilles to run the 100 meters the tortoise majestically crawls 10 meters. As Achilles runs those 10 meters the tortoise crawls one meter. So for any given period of time, the tortoise always covers 10 percent of the distance that Achilles does. Zeno declared:

“By this logic, Achilles will never truly catch the tortoise. Every time he gets closer, the tortoise is always a little further ahead. Does this mean that motion itself is impossible even though we experience it daily?”

I can see a flaw in this example: a race has a finite finish line over which the first person that crosses wins the race. If the race was over 110m, then yes, the race would be won by the tortoise. But as the distance becomes further, the gap between Achilles and the tortoise becomes shorter. So short, that Achilles stride length will reign supreme! Alas, the flaw in my flaw is this paradox focuses on the logical argument (and not real-world physics) that Achilles, to overtake the tortoise, must first reach the point where the tortoise started. By the time Achilles reaches that point, the tortoise has moved forward. This process repeats infinitely, seemingly implying Achilles can never actually pass the tortoise.

Moving on in time and to the world of 1960s American game shows, we have the Monty Hall Problem. Though seemingly a paradox, it can be solved using basic probability mathematics. The problem revolves around the show’s finale ‘Open the Door’ segment. There are three doors and only behind one of them sits the grand prize (you have a one-in-three chance of winning the top prize). The contestant picks a door they would like to open. The presenter - Monty Hall - will open one of the other two doors always revealing a lesser prize. You’re still in with a chance to win the top prize: your odds of winning have now jumped to fifty-fifty. Right? You can now either stay with your initial door choice or select the other unopened door. If you stay put your odds of winning were one-in-three if you switch doors then it jumps to two-in-three right? Your maths skills will help answer this paradox.

A final paradox to chew over involves a cat and quantum mechanics. The simple version begins with the idea that a cat is placed in a soundproofed wooden box. Now, without lifting the lid to observe the cat, how do we know whether the cat is alive or dead? Physicist Erwin Schrödinger came up with this thought experiment in 1935 in response to the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics:

‘Until we observe a particle or thing, it exists in all states possible. Our observation determines its state.’

Returning to our cat in a box, a more sophisticated version is to add a jar of cyanide, a hammer, and a Geiger counter along with just enough radiation so there’s a 50/50 chance of the Geiger counter being triggered within an hour, releasing the hammer to crack the jar and thus poisoning the cat. We can use science to tell us plenty about each particle of the cat, the box, the jar and the odds that a particle may have decayed radioactively. But science cannot tell us anything about the state of the cat until it’s actually observed. So if the hour goes by without observing the cat, the animal is theoretically both alive and dead - which we all know is absurd and impossible: a paradox. Without observation, we can never be 100 percent sure of a current state. Similar to those heaps of sand, at what point can we assume that things we cannot directly observe actually exist in an expected state? Experience informs us of that certainty but that is not the same as empirical observation.

Returning to our 14th century French philosopher, Jean Buridan: apocryphal stories3 abound. Whilst relating to his reputed amorous affairs and adventures, he still had the time (and energy) to teach logic and philosophy at the University of Paris. His ass thoughts were an education on free will and as Amy and Sheldon alluded to in the above clip, Buridan’s thoughts were a riff on Aristotle and al-Ghazali:

“…a man, being just as hungry as thirsty, and placed in between food and drink, must necessarily remain where he is and starve to death. — Aristotle, On the Heavens, c. 350 BC”

“Suppose two similar dates in front of a man, who has a strong desire for them but who is unable to take them both. Surely he will take one of them, through a quality in him, the nature of which is to differentiate between two similar things. — Abu Hamid al-Ghazali, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, c. 1100”

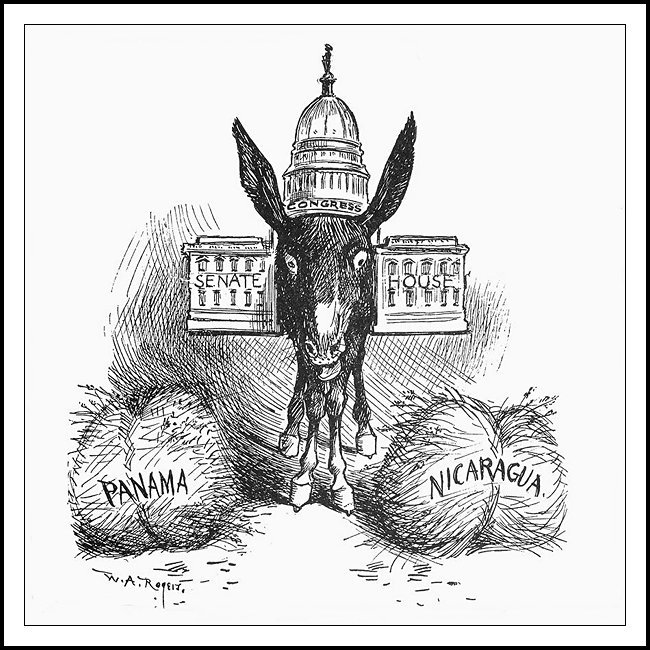

Buridan’s Ass came much later, though earlier than the satirical cartoon above. The apostrophe s denotes possession, but Buridan’s Ass was not his to own. Buridan spoke about two courses of action judged to be morally equal. His thoughts were later satirised and an ass was used by way of example. This example then gets modified to such an extent that a ass will die because it cannot choose between two identical piles of hay.

The paradox of Buridan’s Ass, for me, falls on its ass as no paradox exists. Buridan’s original musings are clear and non-paradoxical. If presented with two equal courses of action then more information must be obtained or received until a decision can be made. This is fine. However, you do need to consider the use of language and what is meant by equal? Similarly, when the ass analogy is rolled-out, words such as identical are also introduced. Language wise, identical rings a little of Eubulides’ heaps of sand. At what point is a heap, linguistically or logically, no longer a heap? At what point is a pile of hay identical to another one?

Buridan’s Ass assumes everything is identical: the distance between the ass and the hay is identical; the terrain to each pile of hay is identical; the size and quality of the hay is identical; etc. This is never the reality. As the ass sits and pontificates over the merits of each pile of hay, a small gust of wind blows a couple of pieces of hay from one pile. The ass sees this and starts walking towards the larger pile of hay.

At a finite point in time the ass was unable to choose and without observation may well have been dead (Schrödinger’s cat!). But time gallops on (much to Zeno’s Achilles’ dismay), hay piles alter and hunger pains wane. Jean Buridan’s initial contemplations were not paradoxical. Buridan’s Ass only smells a little like a paradox if we suspend our understanding on how time moves and things change. Ultimately, Buridan’s Ass, and paradoxes more generally, enable you to run your brain in top gear and cogitate: that is an exemplary endeavour. If you think and keep challenging with ‘Why?’ then you are well on the road to becoming a philosopher! Whilst you’re in gear to think then perhaps the more linguistically minded readership will be asking ‘Why not Buridan’s Donkey?’

Don’t get me started on why is Amy calling it an eggplant?

-

Philosophy comes from the Ancient Greek words philos meaning love and sophia meaning wisdom. So by nominative determinism, Sophia Love should be a rock star philosopher? Go search for yourself if interested… ↩︎

-

Sarah asks one of the guards: “Would he [pointing to the other guard] tell me that this door [pointing to one of the doors] leads to the castle?” She then takes the other door. ↩︎

-

A story which is probably not true or did not happen, but which may (paradoxically) give a true picture of someone or something. ↩︎